Never the twain shall meet?

Constructing religion and homosexuality in the media

Mariecke Van den Berg

Puedes consultar el AUDIO, VÍDEO, PRESENTATION (pdf in English), CONFERENCE (pdf in English), CONFERENCIA (pdf en español) y CONFERENCIA (en línea en Español) de esta ponencia o las II Jornadas completas.

I would like to tell you a bit more about the research project that I am working on, titled “Contested Privates, the oppositional pairing of religion and homosexuality in public debate”.

In this project, my colleagues and I are investigating why religion and homosexuality are always seen as each other’s opposites in the media, and why they form are such an “explosive” combination. I think that the Netherlands are known throughout the world, or like to be known, for their high level of acceptance of homosexuality. You probably know that Netherlandswere the first, in 2001, to introduce same-sex marriage, after having introduced registered partnership in 1998. Already in 1986, one of the many church denominations decided to bless same-sex relationships. In 2004, the ProtestantChurchof the Netherlands, the largest Protestant denomination, decided to do the same. LGBT organizations have a long history of getting state support. LGBT rights have become an important export product of the Netherlands, with all its positive and problematic side-effects.

In this project, my colleagues and I are investigating why religion and homosexuality are always seen as each other’s opposites in the media, and why they form are such an “explosive” combination. I think that the Netherlands are known throughout the world, or like to be known, for their high level of acceptance of homosexuality. You probably know that Netherlandswere the first, in 2001, to introduce same-sex marriage, after having introduced registered partnership in 1998. Already in 1986, one of the many church denominations decided to bless same-sex relationships. In 2004, the ProtestantChurchof the Netherlands, the largest Protestant denomination, decided to do the same. LGBT organizations have a long history of getting state support. LGBT rights have become an important export product of the Netherlands, with all its positive and problematic side-effects.

Religion and homosexuality in the media

Still, we have recently had some very strong debates on homosexuality, and in all these debates religion was an important factor.

Perhaps surprisingly, same-sex marriage itself was never much of a discussion. We had it coming for a long time. There was a lot of attention in the international media for the first gay wedding, but not in the Netherlands. But after the introduction of same-sex marriage there was a huge debate about what to do with “marriage registrars with conscience objections”. The question was what to do with religious, mostly Christian, civil servants who based on their religious convictions refused to marry same-sex couples. Should they, as representatives of the neutral state, be forced to choose to perform these marriages or be fired? Or should they, as members of a religious minority, be protected?

The second debate came with the growing number of Muslim migrants to the Netherlands. Especially by right-wing parties, Islam has come to be seen more and more as a threat to our “Judeo-Christian” values. For the sake of simplicity and despite more complicated reality, they include LGBT acceptance in these values. But debates really started happening when imams, often referred to by the media as “hate-imams”, would preach against homosexuality. What counts more, people wondered, freedom of religion and speech, or the protection of LGBT’s against discrimination?

Thirdly, there were debates about whether or not Christian schools were allowed to fire staff when they turned out to be in a same-sex relationship, against the code of the school. What was to carry more weight, the legal rights of these teachers, or the rights of a school to organize itself around its own religious principles?

It seemed to us that religion and homosexuality had traded places. In the past, religion was a self-evident part of the public sphere, while homosexuality was something for the privacy of the bedroom. Now, religion is suspect, something you practice at home and cannot show in the public space, while homosexuality has become very visible, during Pride, but also on TV.

In our project we started wondering two things. The first is: are the debates as we know them in the Netherlandsparticular for our country? The Netherlandshave been characterized by religious diversity but also by a long history of Calvinist dominance. Are debates different in countries with a different church history and political climate, and if so, how are they different? And, second, why homosexuality? Why is this topic, of all possible topics, so controversial, why does it get so much attention in the media, especially when we add religion?

In order to answer these questions, I was given a sub-project in which I compare debates in the Netherlandsto debates in other countries in Europe, with a focus on Serbia, Sweden, and Spain. We chose these countries because different forms of Christianity are dominant there, or have been dominant in the past: Eastern-Orthodoxy in Serbia, Lutheranism in Sweden, and Catholicism in Spain. During the course of the research, other countries were sometimes included.

In this research I use the method of discourse analysis. A discourse can be described as a set of ideas that fit together well, that make a coherent story based on a certain ideology. A conservative Christian discourse on homosexuality can for example be that God condemns homosexuality in the Bible and that it is a threat to the family. A progressive discourse can be that God created diversity, that we should therefore see sexual diversity as a blessing. In discourse analysis, we are interested in how power works through language. Words can be powerful when they are spoken by a person with much authority, like a politician or a bishop. They can be powerful when they reach a big audience, for instance on the eight o’clocknews. And they can be powerful when they evoke certain emotions among the public. Take the national anthem of the Netherlands. In the national anthem we sing, believe it or not: I am William of Nassau, I am of German blood, and I have always been loyal to the King of Spain. I won’t bother you with the historical context in which these words made sense. My point is that the words of the anthem are powerful, because they are the anthem. Sometimes someone will want to change the lyrics, because not a lot of people feel loyal to the king of Spain, I doubt many people in the Netherlandseven know his name. But then there will be much resistance. People are emotionally attached to these words. Likewise, people can become emotionally attached to a certain discourse on homosexuality. To them, the way they speak about homosexuality has become attached to other things they feel strongly about emotionally, like their country, their religion, their position in society. I will talk more about that later. For now, what I am interested in in my research project, is which words are being used, how power works through them via 1) authority, 2) the reach of the medium, and 3) the emotions that are attached to them.

Case Studies

1) The Antichrist is gay: Russia

Since we are talking about words, I would like to give an example of a country where one word has become very central, and that is Russia. In particular, I would like to get into the use of the word Antichrist on the Russian internet. More and more Russians become active on the Internet, and this is where much ideology, both nationalistic and otherwise, is being spread.

As you probably know, the Antichrist is found in the book of Revelation in the Bible, where this term is used as a synonym for Satan, who will rule the world before the second coming of Jesus Christ. My colleague Magda Dolinska-Rydzek is writing a dissertation on the Antichrist, not the most cheerful topic for a dissertation I guess, but a very interesting one. Together with her I have analyzed the effects of using this figure as a way to describe LGBT-people, mostly on Russian nationalist websites.

Let’s first have a look at a quote on how the Antichrist is being connected to LGBT people.

Kiryll, the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, states the following:

The Antichrist will teach evil, teach that killing and violence are good. One would think: who would accept such a leader? However, today, it is being implemented in our consciousness that there is no objective difference between sin and virtue as in many countries same-sex marriages and normal marriages are legally placed on the same level.

There are many more examples of usage of the figure Antichrist in relation to homosexuality. At first I was quite shocked by the use of the term. In my own tradition, which is Calvinist protestant, the word itself is almost too scary to pronounce. When I was young, saying the word may make the Antichrist himself appear. Equating people with the Antichrist is not something church leaders in the Netherlandswould easily do, leave alone in the media. It would be considered too strong.

There are, however, many examples of the use of the Antichrist in Russia, when you dig into its history. The Antichrist is seen in individual figures such as Napoleon, Rasputin and Peter the Great. In political and social systems such as Russian autocracy, socialism, communism or liberal democracy. And in social groups such as Roman Catholics, Jews, Muslims and (other) immigrants. Each epoch of Russian history created its own version of Antichrist, versions which often have little in common with the Beast from the Book of Revelation. And now, finally, the Antichrist is gay. Since it has been used to denote so many different things, I suspect that the term has suffered some inflation and is not terrifying Russians as it would have terrified twelve-year-old me. In that sense it is less rhetorically powerful.

On the other hand, the term currently not only refers to gays and lesbians, but also to the West, sometimes to the Pope, basically to everything that is perceived as anti-Russian. The Antichrist, in short, is that which is “other”, the non-we, the not-Russian. The Antichrist is a powerful term in the sense that it is the glue that holds all these perceived anti-powers together. The Antichrist works as an umbrella term for everything that is perceived as a threat to Russia, and it makes it possible to divide the world up in a simple “pro” or “con”. You are either supporting Russia, tradition and family. Or you are supporting the Antichrist: Europe, the United States, homosexuality, promiscuity and the break-down of the family. Through the Antichrist, religion becomes strongly connected to nationalism, loyalty, anti-Westernism. It then becomes very difficult for LGBT activists to struggle for equal rights. Such a struggle is suspect, because their loyalty to their country and the Orthodox tradition are also immediately suspect.

2) The Gospel according to Conchita

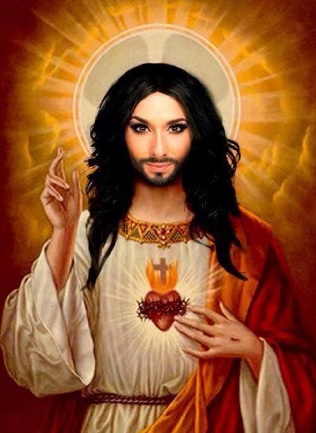

I would like to move away from Satan right now, and move to a more cheerful stage where all of Europe comes together, that of the Eurovision Song Contest. As you probably know, the Eurovision Song Contest until not too long ago was a sort cover-up for LGBT-folk. Saying you liked the contest was like a secret hint that you were gay. Now, it is more openly a queer thing, especially after transgender Dana International won for Israel. In fact, things have turned. Busloads of LGBT-people go to visit Eurovision like going on a school field trip. It is now in your benefit to have a bit of a queer performance, to play with homosexual themes on stage. Still, cross-dresser Conchita Wurst who won last year was a big deal. You may remember her as the “woman with a beard”. In most Western countries, the media paid a lot of attention to Conchita’s personal story. Conchita was born as Tom Neuwirth in Austria, identified as gay from an early age on, and was bullied in high school. After her coming-out, she became a performer, feeling very comfortable in a dress AND with a beard. The winning song, Rise Like a Phoenix, was about this victory over rejection and finding herself. In the East, the topic in the media was very different. In Russia, people thought Conchita was a disgrace. A campaign was started on social media for Russian men to shave their beards. This sign of masculinity had apparently become contaminated with femininity after Conchita. But what was most troublesome for people in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, was the resemblance between Conchita and Jesus. Irinej, the patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church, blamed floods in the Balkans to what he called “this Jesus-like figure”. In the West, only very few people had thought of Conchita as Jesus. Some made an occasional joke, like: Conchita is a crossing between Angelina Jolie and Jesus. But none took the religious symbolic very serious. But the religious interpretation is not so weird. [Slide with iconic Conchita.] Conchita does remind us of Jesus, especially as we know him from icons and from pictures in children’s Bibles. But it is not just the face. The whole song played with the idea of resurrection: Rise like A Phoenix, it is both in the text as well as in the light and the staging of the show. And it is especially the mixture of cross-dressing and Christianity which is seen as problematic in Serbia and Russia. Apparently, in these countries the church prefers a masculine Jesus. What Conchita confronts them with, though, is that in the Christian tradition, Jesus has never been simply masculine. He is often pictured in a feminine way in Orthodox tradition, and not only there. Jesus is often pictured in a way that in our culture is perceived as feminine: long hair, a dress, together with a little lamb or with children. Conchita confronts the church with an image of Jesus that is already there.

I would like to move away from Satan right now, and move to a more cheerful stage where all of Europe comes together, that of the Eurovision Song Contest. As you probably know, the Eurovision Song Contest until not too long ago was a sort cover-up for LGBT-folk. Saying you liked the contest was like a secret hint that you were gay. Now, it is more openly a queer thing, especially after transgender Dana International won for Israel. In fact, things have turned. Busloads of LGBT-people go to visit Eurovision like going on a school field trip. It is now in your benefit to have a bit of a queer performance, to play with homosexual themes on stage. Still, cross-dresser Conchita Wurst who won last year was a big deal. You may remember her as the “woman with a beard”. In most Western countries, the media paid a lot of attention to Conchita’s personal story. Conchita was born as Tom Neuwirth in Austria, identified as gay from an early age on, and was bullied in high school. After her coming-out, she became a performer, feeling very comfortable in a dress AND with a beard. The winning song, Rise Like a Phoenix, was about this victory over rejection and finding herself. In the East, the topic in the media was very different. In Russia, people thought Conchita was a disgrace. A campaign was started on social media for Russian men to shave their beards. This sign of masculinity had apparently become contaminated with femininity after Conchita. But what was most troublesome for people in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, was the resemblance between Conchita and Jesus. Irinej, the patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church, blamed floods in the Balkans to what he called “this Jesus-like figure”. In the West, only very few people had thought of Conchita as Jesus. Some made an occasional joke, like: Conchita is a crossing between Angelina Jolie and Jesus. But none took the religious symbolic very serious. But the religious interpretation is not so weird. [Slide with iconic Conchita.] Conchita does remind us of Jesus, especially as we know him from icons and from pictures in children’s Bibles. But it is not just the face. The whole song played with the idea of resurrection: Rise like A Phoenix, it is both in the text as well as in the light and the staging of the show. And it is especially the mixture of cross-dressing and Christianity which is seen as problematic in Serbia and Russia. Apparently, in these countries the church prefers a masculine Jesus. What Conchita confronts them with, though, is that in the Christian tradition, Jesus has never been simply masculine. He is often pictured in a feminine way in Orthodox tradition, and not only there. Jesus is often pictured in a way that in our culture is perceived as feminine: long hair, a dress, together with a little lamb or with children. Conchita confronts the church with an image of Jesus that is already there.

Conchita is not the first one to mix a woman with a beard with religion. Some journalists pointed at the story of Saint Wilgefortis, also known at the Ontkommer. According to this story, there was a maiden who, against her father’s will, refused to marry. She wanted to devote her life to God instead. Her father became angry and wanted to force her to marry anyway. She then prayed to God to let something happen that would prevent her from getting married. She woke up the next morning with a beard. No-one wanted to marry her after that. Her father became so angry that he said: now you will die the way this Jesus that you worship also died! And she was crucified. I love the commonalities between this Saint’s story and Conchita. Both have become an in-between person. Both reject the traditional form of relationships. Both felt that they were doing the right thing.

Conchita is not the first one to mix a woman with a beard with religion. Some journalists pointed at the story of Saint Wilgefortis, also known at the Ontkommer. According to this story, there was a maiden who, against her father’s will, refused to marry. She wanted to devote her life to God instead. Her father became angry and wanted to force her to marry anyway. She then prayed to God to let something happen that would prevent her from getting married. She woke up the next morning with a beard. No-one wanted to marry her after that. Her father became so angry that he said: now you will die the way this Jesus that you worship also died! And she was crucified. I love the commonalities between this Saint’s story and Conchita. Both have become an in-between person. Both reject the traditional form of relationships. Both felt that they were doing the right thing.

Finally, Conchita also plays with theology. For Conchita, resurrection is about coming-out. About becoming not who people want you to be, but who you really are. I just love the Gospel according to Conchita!

East and West – never THOSE twain shall meet?!

That religion and homosexuality are topic of debate is not specific for the Netherlands, it happens in in many countries, but the exact themes are different. When a debate starts depends on whether we are in a mostly secular or Christian country, and if we are in a Christian country, which church denomination is dominant. In this, there seems to be a dividing line between the secular West and the Orthodox East. We can see this also when we look at the way in which people thought about the Pope, both present Pope Francis and previous Pope Benedict. Benedict was very unpopular in the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries. We thought he was a scholar, a conservative, anti-gay. We thought his ideas about the family were backward, and if he would mention homosexuality only the slightest bit, the newspapers would be filled with articles rejecting his statements. In the East, he was much more popular, even in Orthodox countries where they found that his ideas on the traditional family matched their own ideas. Francis, on the other hand, is very popular in Western Europe. Ever since “the interview on the plane” he can do no wrong in western eyes. Francis had said: if a person is gay, and seeks the Lord, who am I to judge him?” Later he would also utter more problematic statements, but these were ignored by the western media. In Eastern European countries like Bosnia, Francis was ignored altogether. Not using words is also a form of using power: not quoting someone, even if he is the leader of the largest church in the world, means not giving him a voice. Either way, on both sides people created a Pope as they would like to see him, supporting ideas they find important.

This brings me to another point: East and West need each other in the story they like to tell about themselves. Homosexuality and religion give them the opportunity to tell this story, by framing yourself against the other. The West needs the East to portray itself as a tolerant, progressive, coherent “we”, an imagined community as Benedict Anderson has called it. The East needs the West to create a traditional, loyal, coherent “we”. What gets lost is nuance. It becomes different when you talk to people in these countries. I have met LGBT Christians in Sweden who feel excluded by their church. I have met LGBT activists in Serbia who tell me that the church is not as powerful as it often looks in the media. Things are never that simple.

We, LGBT Christians, have an important role to play here. We are the living proof that religion and homosexuality are not necessarily each other’s opposites. We can have an important voice in the debate and counter too simple statements about religion AND about homosexuality. If we do, we need to be aware of the power of language. If you take part in the debate, don’t get caught in the us-them logic. Find your own creative language, invest time in your own interpretation of the Bible. Find basic beliefs, operate from those, and be loyal to them. Read the Gospel according to Conchita. What does the resurrection mean to you? The Exodus? The Creation? Loving your neighbor as you love yourself? Find those things out, write a press release and use your power!

Questions?

Points for discussion:

1) What are major debates on homosexuality in Spain? Does religion play an important role there?

2) What were the responses to Conchita in Spain? And to the Pope(s)?

3) There seems to be a clear East-West divide in Europe. What about Southern Europe? How can it be characterized, what is specific for Spain?

4) Would you want to become an active participant in public debates? Why (not)? What would you want to add to current debates?